There are two main types of HEMA teachers – the ones I like and the ones I don’t.

British instructor Tea Kew is firmly in the first group. Founder of Cambridge HEMA, but now training at New Cross HEMA in London, Tea is a well-known face at international events, both as a fighter and instructor. He has taught in both Europe and across the Atlantic, and I’ve had the pleasure to take part in his HEMAC Dijon 2018 class.

Tea is one of the key modern interpreters of the Liechtenauer tradition, an authority in analyzing the glosa of Sigmund Ringeck. You can see some of his work in the completed “Illustrated Ringeck” project on Facebook.

He is also a historian by education, one of the leading names in HEMA pedagogy and, finally, an exponent of cutting practice and test cutting, which is the main topic of this interview.

Most people would assume we will jump right into test cutting in this interview. However, I feel there is a question that has to be discussed first and is actually more important – tell me if you agree. How do we train cutting in HEMA, as in the mechanical action of delivering a blow?

This is super important. The best way to train cutting is mostly in the air. It’s useful to also work with a pell, to practice engaging the body to deliver power to a target. Test cutting is a test of the cutting training you’ve already done, not the way you train the movement itself – nobody is going to do their ten thousand cuts with a sharp sword and a target for everyone.

It also relates to a really common misconception, which is “I don’t have a sharp sword so I can’t train cutting”. A good cut is just a movement of the sword in a certain way – you absolutely don’t need a sharp sword to make that movement, or a tatami mat to make it through. One of the very best pieces of cutting training I’ve ever had was spending an hour with Karl Bolle swinging swords in the air.

Glad we agree on that! So cutting in the air or against a pell is the main way to train. But how do we check ourselves, if we don’t see a tatami mat splitting in half?

Watch and listen. A good cut will produce a clear sharp whistle throughout the whole cutting arc. If there’s an area in the arc where the sound is dull, that means the edge is probably misaligned there. If there’s an area where the sound is quiet, then the sword is moving slowly. You can listen to this for yourself, or have your coach/training partner watch you cut and tell you where the issues are in the sound.

Different swords are more or less noisy – if you have a very quiet feder, it may be difficult to use this as a form of feedback in a noisy training hall. Then you’ll have to pay really careful attention. In the long run, even if you can’t own a sharp it’s worth getting a nice loud blunt that’s good for cutting practice.

What about cutting at a hard object? Won’t a pell that stops our blows create a bad habit? In fact, when we train against a pell, do we cut at it or through it?

Anything can create a bad habit if it’s your only form of training. One of the big advantages of using a pell is precisely that it stops your cut for you – that’s something which happens in fencing (for example, it gets parried) but doesn’t really happen when cutting the air. Obviously, you can stop it yourself, but that requires changing the movement of the cut in a way that’s not really optimal for getting through a target.

What you’re using a pell for is to get direct feedback on how engaged your body is in the strike at this point of impact. It tells you if you’re firmly supporting the sword and powering that movement from your core, or if it’s just being flicked out by your hands in a way that’s fast but weak against any sort of solid target. So I teach people to cut against a pell as if it would pass through – although of course, the sword will actually stop. One thing which is also useful is to change where you are standing in relation to the pell – by doing this, you can change which part of the cut you’re in when your sword is stopped, which is great for making sure that you are committing to a good cut throughout the whole action.

So our first steps into cutting are, not surprisingly, doing a lot of cutting, even without a sharp. Is there any other exercise that we can try before we have a chance to get a sharp? Do we hit a wall at a certain point if we don’t have one?

I think this is an important question, especially considering some people live in jurisdictions where getting a sharp is problematic, like Italy.

This depends a lot on the quality of your instructor. If you have an instructor who knows how to cut and can watch your actions and give appropriate feedback, then you can get a really long way without ever touching a sharp sword yourself. If nobody in your organisation has the ability to try it, then you’re going to hit a point where you don’t know what to look for to improve/correct without test-cutting.

There is clay, though – that can be cut reasonably well with a blunt to test some parts of good cuts, which helps give some extra options without investing in the expense (and potential legal issues) of a sharp sword.

Okay, we save the money, our glorious sharp arrives, what do we do – do we jump up and down with it for 10 minutes, call some mates from the club, grab tatami or whatever we can find and go cutting?

Well, first we go back to practice in the air, but with the glorious new sharp. Get used to how long it is, how heavy or agile it is, that sort of thing. Especially if you’ve only handled blunt swords, when you first get a sharp you can be in for a real surprise in the fine details of how it handles.

Once you’re comfortable and familiar with it – you get good sharp clean whistles swinging it through the air, that sort of thing – then roll up some mats and get to testing.

Tatami mats are not exactly cheap and they are not exactly great in value – 4-5 cuts at most for 10-20 bucks is not ideal. Can we learn anything useful from budget cutting mediums like water bottles or soaked paper?

A little bit. Soaked paper is apparently quite good, but I haven’t actually used it myself so don’t have a detailed opinion. Water bottles are very light targets, but good for testing edge alignment and speed at a point. Especially with easy targets like water bottles, it’s important to be super picky about the results. Nearly any cut that’s halfway aligned will get through a water bottle, so make sure it’s so perfect that there’s not even a splash.

There’s a lot more to learn from when you cut tatami than just the act of swinging a sword at it, of course, but I think that might be your next question 😉

I will surprise you a bit and push you first slightly close to the critique that comes against test cutting. But not directly – when we start cutting, how do we go at it? Most people see test cutters using the widest guards possible – sword above the head, far to the side, etc. Do we do that, or do we assume the typical positions we have spent so much time cutting in the air from, like a sword on the shoulder (Vom Tag/Posta di Donna)?

Learning nearly any skill is about starting easy and making it harder with practice as you gain competence, and cutting is no different. So start with your optimal situation – for me, that’s actually at the shoulder (I’ve practiced it so much more I have better body engagement) and make it as easy for yourself as possible. When that’s consistently working, then make it harder – use a heavier target, a tighter guard, add other movements or requirements, etc.

Okay, I will bite now – what do you mean by learning more from tatami than to just swing a sword at it? Isn’t it just a medium to test our edge alignment on?

The first question with swinging a sword at a mat is “did it go through?”. But basically, anything with reasonable edge alignment and some decent velocity will get through a few inches of wet grass – so stopping at that point means we’re missing a lot of the detail that you can learn from the behaviour of the mat.

One of the most useful things about tatami as a cutting medium is that it gives very clear feedback about the cut. The path that your sword took through the mat is clearly shown in the remaining piece, and the trajectory of the severed part tells you a lot about the details of your cut. In a ‘perfect’ cut, the path is completely straight and the severed piece will slowly and gently slip/fall down to the ground. Any deviation from this indicates an issue that we can work on improving – and where tatami really shines is that most of the major issues each produce a different result, so you can diagnose which problems you’re having.

For example, if the severed piece falls away from the cutter, that’s generally indicative of a cut where the tip is lagging behind the hands – resulting in a force that pushes away. By contrast, if the severed piece falls towards the cutter, it often means the tip is ahead of the hands and the wrists are overextended – resulting in a hooking action. Other results (spinning flying off, curved arcs in the remaining mat, etc) each correspond to their own issues.

As a result of all this, we can learn an awful lot more from cutting a mat than just “was my edge alignment good enough to get through”. Especially with video recording being so accessible now, it’s very easy to film your test cuts and then go through them later and diagnose exactly what’s going on in each one, to work out training points to take into your practice. I still have the film of the very first mat I ever cut – and it’s still useful occasionally when I notice I’m making old mistakes again.

You do? Would you like to share it?

Sure!

Here come the dreaded questions that always pop up with HEMA – what about tournaments? I myself have had doubts about regular HEMA tourneys before I started going. But even after I realized that some of the critiques are fair – there are people who go to just bash others, or throw themselves in for a point, or game the rules as much as they can, although they are much rarer than it seems.

Cutting tournaments don’t directly oppose you against others. Yet there seem to be tournament conventions forming now. How do we cut at tournaments to get the most out of it for our training?

Much like with sparring tournaments, most of this is about attitude. You need to look at it as a test of your training and a source of feedback. I’ve competed in one cutting tournament and I learned an awful lot about what actions I could reliably make work in test cutting, as opposed to actions I thought I had down but couldn’t do every time under pressure.

Most cutting tournaments are designed in a similar progression to the way you should be test-cutting anyway – simple and easy actions to begin, with further rounds testing more difficult cuts and more difficult scenarios for applying cuts. So even if you’ve never had an opportunity to swing a sharp before, you can actually get a fair amount out of a cutting tournament, as long as you’ve been training to cut effectively.

Oh, and make sure to get someone to video you so you can review it!

So you approve of the current tournament formats? Would you change anything if you had a chance to organize a test cutting tourney yourself? Or am I asking you to reveal future plans? 😀

As it happens, I’m running a test cutting tournament just a few days after we’re talking, down in Exeter in the southwest UK – and then competing in Longpoint’s longsword cutting at the end of March. So I might have more opinions about how to change stuff once those are done. 😉

Overall I think the current tournament formats are pretty good for people who approach them with the right attitude. One of the advantages of not being based on direct competition is that you don’t get the frustrating expectation/style mismatch that can happen in sparring sometimes.

The most obvious space for development is in judging. When I was preparing the rules and scoring for Exeter, I got some excellent advice from Sean Franklin:

“Have a good idea of the judge’s capabilities when designing rules. You can design all the criteria in the world, but if judges can’t recognize them consistently, it does you no good.”

Better judges make more interesting challenges available for round design.

Another area I’m keen to see explored are challenges for lighter swords. Rounds requiring very quick multiple cuts or cut transitions, short arc cutting, etc. There’s a bit of a tendency at the moment for people to favour very heavy and powerful cutting swords, which aren’t necessarily super representative of typical swords for a lot of the sources we study but are very effective when most of the tests are a bit more focused on power and consistency. Having some more tests which favour quick movement between cuts should be a nice way to help diversify that a bit.

Sounds no different than regular sparring tournaments in that regard.

Fundamentally, a cutting tournament is just like a sparring tournament – it’s a test of our training. Approach it like that and there’s a lot to learn – treat it as a game to win and you’ll be losing out on a lot of the options.

Do you think meat cutting is something people should try? Or ballistic gel? Is there a value in looking into more “realistic” cutting targets that are closer to human flesh?

I haven’t personally tried either. The folk I know who’ve tried ballistics gel say it’s not really formulated for blade testing, so I don’t think there’s much value there. Meat is more interesting – obviously if treated right it can be very realistic, but the trade off there is consistency. Which is actually quite realistic in itself, since the effects of a cut depend hugely on precisely where it’s delivered. There’s probably value in it as a limited component of training, just to get that extra bit of familiarity (and practice extracting a stuck blade).

We have clearly established that training cutting is essential, and test cutting is something we should do at a certain point. But do we need it regularly? What actually is “regular” test cutting?

Pretty much any form of HEMA training is a cycle – we decide what we need to work on, train that thing until we think it’s improved, then test our training. From that test, we decide what to focus on next and repeat the whole process. Test cutting is the test stage of that process, so the frequency depends on how much you train cutting and how fast you can incorporate corrections into your movements. That’s very personal, unfortunately.

For me, I tend to test-cut a couple of times a year. In each one, I spend some time working on evaluating the specific stuff I’ve focused on in my cutting practice, and sometimes testing a variety of other cuts to see where I should be focusing next.

As a club, I like to have cutting quarterly or so, although obviously, not everyone needs to cut every time. Who should cut at a given session is something to be worked out between the instructor and their students.

You already mentioned Karl Bolle and Sean Franklin, two well-known cutters in HEMA. Any other people we should look up online and check how they cut? Any good resources you might recommend?

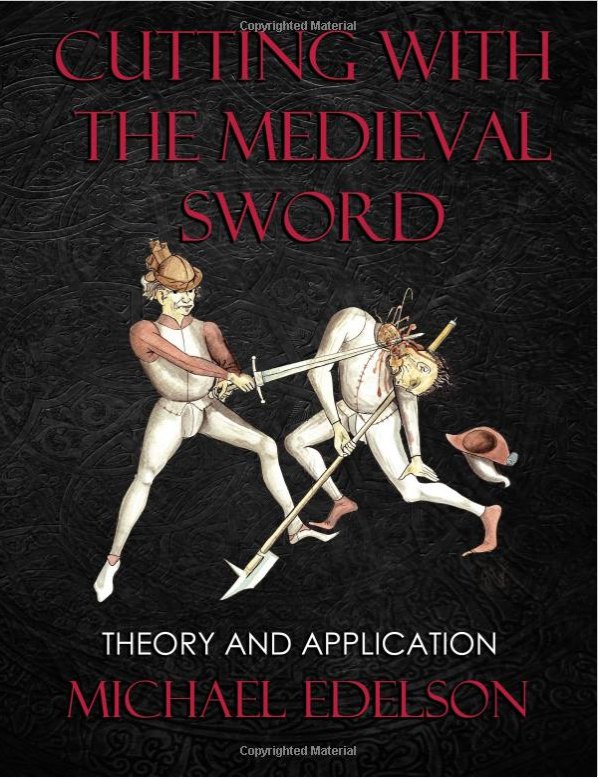

I also mentioned Mike Edelson, the grandfather of HEMA cutting – his book is really a very solid piece of work on this subject and I highly recommend it.

Beyond that, there’s an extremely detailed video series on the fundamental mechanics of effective cutting by Eric Lowe of Swordwind Historical Swordsmanship. He goes through grip, arms, body and leg engagement in excruciating (but very useful) detail. Watching those and practicing exactly what he does is actually an effective way to learn basic cutting if you don’t have a good local instructor.

Once you’ve done some test-cutting – no matter how badly it went – it’s also very useful to join the HEMA Cutting Discussion Facebook group. You’ll need to have a video of yourself to join, but it’s a really solid productive place to ask questions and get tips.

Well… that was quite a talk, Tea. I want to wish you good luck with the tournament you are running, and good fun at the tourneys you will be participating in. Thank you very much for your words. Any last advice you want to add for anyone who wants to get good at cutting?

You’re welcome – it was great to be able to chat about this.

My last piece of advice is “first cut first”: it applies to cutting (particularly the famous ‘double cut’, cutting a mat and then cutting the severed piece) and means that if you’re doing something complicated, don’t worry about the later parts until you’ve got the first part done properly. Great advice for cutting, but also great advice for fencing and even for life in general.