When I started with HEMA, I was eager to find out everything about everything. The Spanish La Verdadera Destreza was one of the few things that remained a hidden mystery – behind a wall of Spanish, never translated, with only bits of info and videos online.

Years passed, and I put Destreza in the back of my mind. One day I met Aleix (it’s pronounced Alesh) Basullas Vendrell, a funny guy from Spain and an experienced Destreza fencer.

Aside from being incredibly knowledgeable, Aleix is also open about it and ready to talk Destreza or fencing in general with anyone. He is also part of one of the first waves in HEMA. “I am not sure when I started HEMA”, he says because he is an example of one of those guys who started with swordfight choreography and reenactment and slowly transitioned to HEMA.

It was in 2008 that he started officially in a HEMA club – AEAS, Associació d’Esgrima Antiga de Santpedor. His first teacher was Sendo Espinalt. He studied longsword, rapier, sword and buckler, and trained with some of the most well-known Spanish instructors. In 2013 he became the instructor of his club, now Associació Esgrima Antiga Catalunya Central, and he teaches at chapters in two towns – Santpedor and Manresa.

To most people in HEMA, “Destreza” is “the weird Spanish rapier where they walk around upright and with the weapon parallel to the ground”. Some are impressed with the geometric circles, others – with the seemingly simple actions, which for some reason need hundreds of pages of flowery language to be described. How do you define what is characteristic of Verdadera Destreza?

While walking upright is indeed by the book, and so are hundreds of pages of flowery language, I feel the most defining aspect of Destreza is that the main strategy is to bind first, then attack if at all possible. Attacks without some kind of preceding contact are few and done quite carefully.

Disarms or at least hilt grabs are also very emphasized, and while they also exist in other systems I haven’t seen as much praise for them elsewhere (they are considered the best action you can take in Destreza, at least if we don’t get into sabre Destreza).

So perhaps I’d say the main characteristic trait of Destreza in practice is controlling the opponent’s weapon.

If we get into what’s characteristic of the books I’d say the focus on explaining why things are correct or incorrect, rather than purely offering practical advice.

Let us make a short historical overview. When did Destreza begin historically, and when did it end?

Destreza proper begins with Jerónimo Sánchez de Carranza, who wrote his book “Of the Philosophy of Arms and it’s Skill and Christian Aggression and Defense” in 1569 (published in 1582), some say inspired by Camillo Agrippa.

However, it’s with Luís Pacheco de Narváez that it becomes extremely widespread, between his many books and using his post as “Major Master” to enforce Destreza on the Spanish fencing masters.

There are many authors for Destreza, with the last one for rapier being Francisco Lorenz de Rada, but Destreza continues on, with a smallsword treatise by Antonio de Brea in 1805, a full century after Rada’s most important book, and some Destreza inspired sabre treatises still in the 19th century, although it’s arguable how much Destreza they really are, besides sharing bits of terminology and claiming to be Destreza.

Interestingly, by the middle of the 19th century, Gregorio Cruzada Villaamil was already trying to reconstruct Rada’s method from his book, without any direct lineage.

Do you have any theories on your own as to what inspired Carranza to develop a system that is on the surface so different than other systems at the time?

To be completely honest I’ve always found Carranza’s book quite impenetrable, being a Socratic dialogue between four friends, so I know little about his actual system, most of it from Pacheco praising him in one book, or criticising him in another.

However, if we take Destreza in general, I think it’s the premise of trying to be a good Christian and obey “thou shalt not kill”. By focusing on control of the weapon and disarming you may be able to, ironically enough, save your aggressor’s life. This might’ve also helped get the books past censorship, and made it more palatable to the higher classes, who tended to view fencing as a low-class activity, but who might appreciate it with the right philosophy behind it, and a matching practice.

Do you think it was an attempt to create a socially acceptable fencing style? Is that also the reason for the heavy emphasis on geometry and scientific reasoning?

That’s very possible I think, with everything contributing to creating an image of a proper science (as was understood back then) rather than just a physical activity.

I will say I do find some of the circles quite useful to learn the positions required for each technique, especially without a teacher to show them, though in some of the earlier books the circles are pretty much shown once and end up rather irrelevant in practice.

For example, Pacheco’s circle as drawn by Rada. Of all the steps only one uses the circle, so I have to wonder if it had any actual use there.

The circles of Destreza are one of the elements that create the idea of a very complex system, yet you say some of them are not particularly useful. Does the same go to some extent for the Right Angle guard, another well-known characteristic of Destreza? When we see diestros fencing, they are in the Right angle pretty much only outside of distance. Does the mathematical perfection of Destreza break in actual fencing?

My feeling is that it works, however, you need to trust it to work, and you need to train properly. I feel a common problem is that Destreza practitioners have a tendency to only fight other Destreza practitioners, and might panic somewhat when faced in other styles then.

For the Right Angle specifically, it can be an issue of people trying to look picture perfect until they actually engage, but also of not finding the right situation for it. The Right Angle doesn’t need to be adopted out of distance, that’s just a nice way to tire your arm, and when in distance it might be adopted rather briefly, quickly going to bind in an appropriate way.

When fighting Destreza against Destreza it’s also common for people to “cheat” and start with their point raised to gain a more advantageous bind from it, but that exposes them to other dangers from non-Destreza practitioners, like lunging under their arm more easily than if they were actually presenting a threat with the Right Angle. If one never encounters that however, the raised point might be more optimal, so the Right Angle quickly gets forgotten.

I cannot continue without asking you about another key Destreza feature – the atajo. For years HEMA diestros have written online about what it is, what it isn’t, and there seems to be a lot of disagreement on this topic. What is your definition of Atajo?

Personally, I like the basic definition: A subjection of the opponent’s weapon such that it has to do bigger movements to wound than the one placing it.

This is a very general concept, however, and then we get into technical details, which is where all the arguments come from.

One thing that I changed my view on when I started reading the treatises instead of trusting second-hand information and which I now find important is that Atajo can be a point offline, and a lot of the time it’s easier to establish like that. The most ideal situation is to be a point in line, but I find most people instinctively know to not let you do that in any way they can.

Another point of contention is whether Atajo can be established from below the opponent’s weapon. Rada is the only one to include that kind of Atajo, and I tend to follow him, but honestly, I’m on the fence. Atajo from below are very useful, the system would be incomplete without them, but I wonder if Atajo should’ve been their name, to begin with.

A feature you see often in early fencing, but even in systems contemporary to Destreza, is motions from below – either cuts or engagements. They are popular in early longsword, messer, than later in the Bolognese tradition. Yet Destreza considers them unnatural movements and diestros are very critical of them. Why is that? Why do you think a whole group of effective movements are suddenly seen as wrong by the Spanish masters?

I would think they follow the premise of downwards being the “best” movement to the logical conclusion. If upwards can always be defeated by downwards, there’s no reason to use it.

This might be untrue for beats, but those are not used in Destreza as they very much depend on the opponent staying put, else they put the user in danger which goes against Destreza’s disdain for actions that might put you in danger. Furthermore, if we assume the Right Angle is indeed the best posture as they did beats will not play any role in the system as you won’t be in a posture to throw them reasonably.

From personal experience, I don’t tend to miss those kinds of actions, or actively avoid doing them. Destreza provides other tools for the situations where you’d want to use them.

Let us talk a bit about Destreza in modern HEMA today. It seems this is the one style that has been largely limited to its place of origin – Spain and Portugal. How far removed is the language in Destreza texts from modern Spanish? Why do you think it is not as popular globally as Italian rapier?

The second question is easy: Until very recently there wasn’t a single fully translated book available, while we’ve had translations for Italian treatises for a long time.

As for the language in the books, it’s quite close to modern Spanish, most of the vocabulary (if not the spelling) is the same, although it might sound old fashioned or very formal to modern ears. I’d say the main obstacle for someone who understands modern Spanish is the way the books are written rather than the language.

I already mentioned Carranza’s book being a Socratic dialogue, Pacheco also has a similar book, although in that case, it’s just a master asking a disciple questions. The rest are just quite verbose, and Pacheco, in particular, is infamous for writing 3 pages about something with the first two being citations of classical philosophers and criticising everybody else.

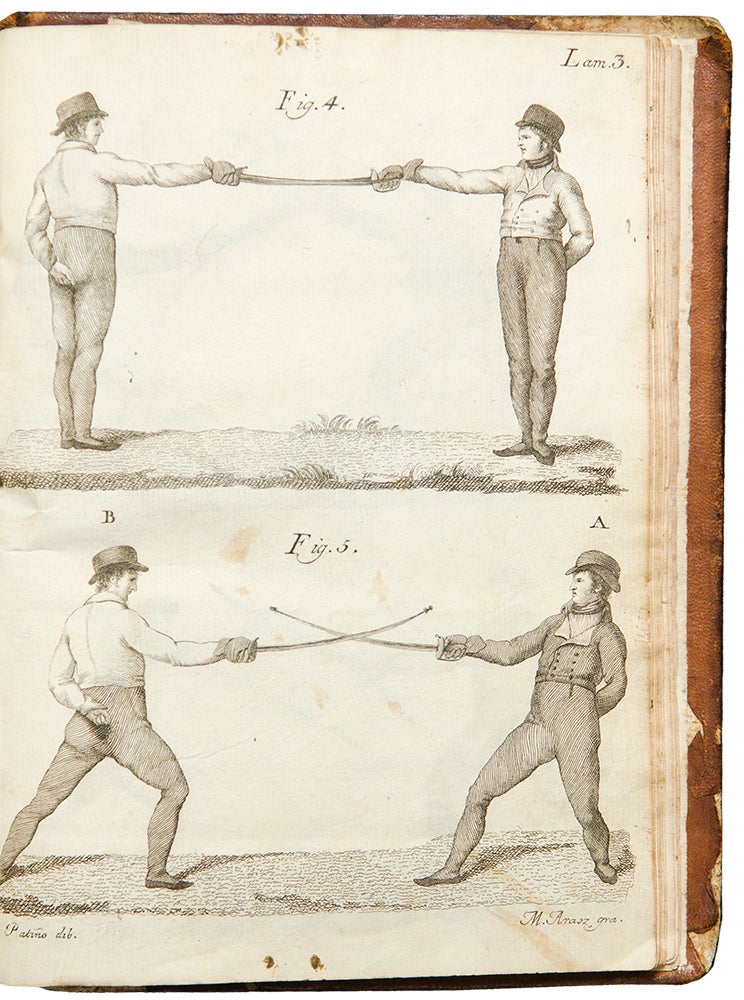

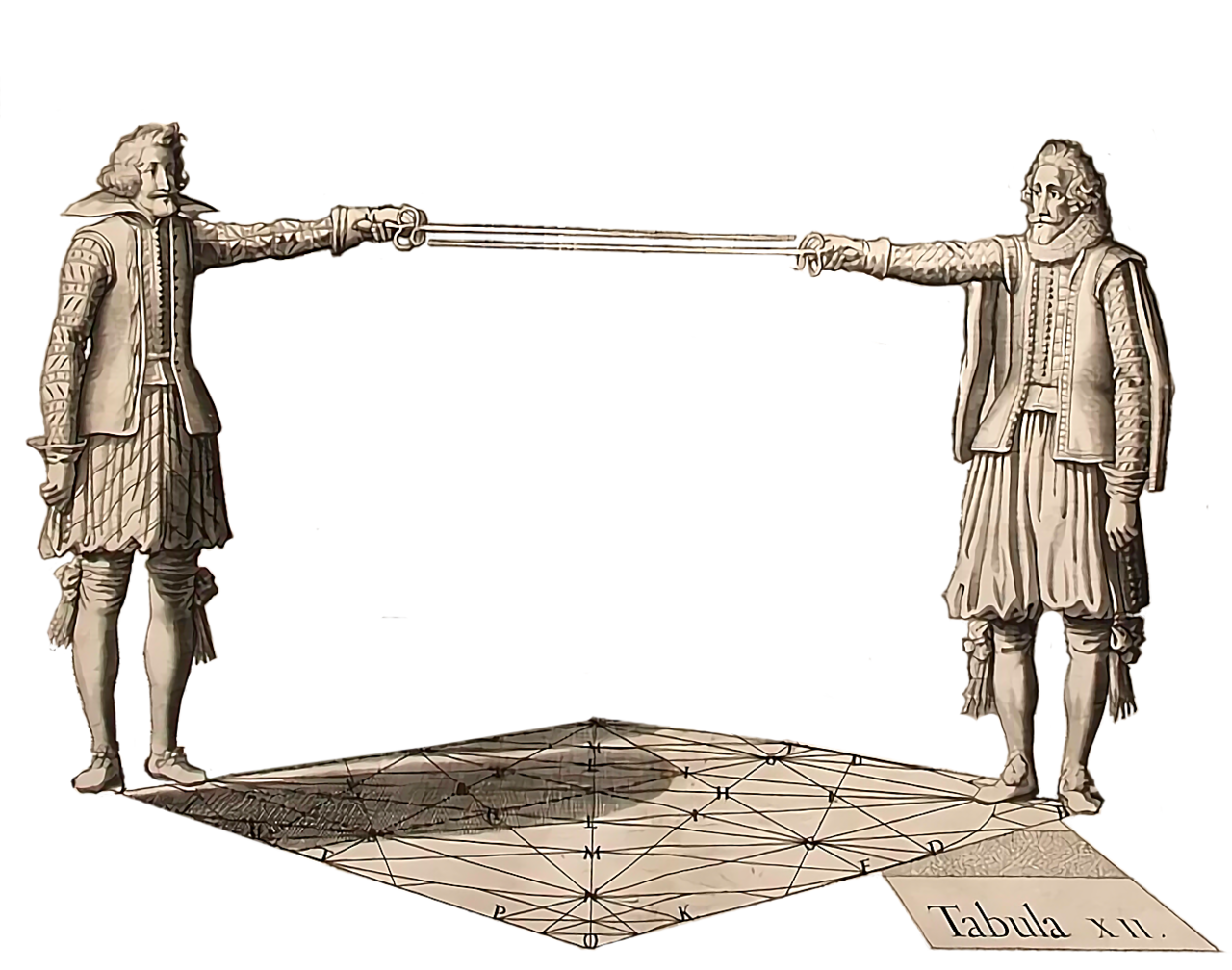

And of course it doesn’t help that most Destreza books are 99% text and if they have pictures they’re often not very fancy, often just showing the positions of the feet and the sword as seen from above instead of realistic depictions of the fighters. Even when they do have more realistic depictions they’re far behind the Italian treatises in quality. The feet positions can be very useful, but they also seem to be quite disheartening to people just starting to read Destreza.

Well, in just the last few weeks, there have been two new books on Destreza announced. Do you think that will make it more popular around the world?

I’m quite sure of it, a lot of interest seems to have been building up over the years, I know of quite a few people who are eagerly looking for any bits of translated Destreza they can find.

Okay, if I want to study Destreza and I have a chance to visit Spain or Portugal, which diestros (aside from you) should I visit and learn from? Are Spanish schools and instructors open to foreign students just coming by? Are there any big events you would recommend?

I honestly don’t know much about what’s going on in Portugal, so I can’t talk about that.

For Spain, I’d very much recommend Ton Puey from Academia da Espada and Aitor Blanco from Sala de Esgrima Francisco Lopez de Rada and Sala de Armas de Castellón, especially if you’re interested in Rada. For Destreza, in general, I’d again say Ton and also add Alberto Bomprezzi from Escuela Madrileña de Esgrima Tradicional, who I’m sure knows a lot of Rada too, but as far as I know, takes more from Pacheco. If you like tournaments, Daniel Mablung from 100Tolos studies Destreza too (albeit perhaps not exclusively) and has performed very well so far.

I’ve never heard of any salle not being welcoming to visitors, although a Facebook message beforehand doesn’t hurt.

For events about Destreza, I’d say the most relevant is probably Destreza Days, which changes location every year and tries to bring Destreza to places where it’s not practised much. In Spain, there are no Destreza specific events that I know of but most usually include some.

The AEEA organizes the “Encuentro Internacional AEEA“. There’s also Bilbao Armata organized by Sala de Armas Fénix, Barcelona Historical Fencing Meeting by the ACEA, the Halbschwert Barcelona tournament which sometimes has Destreza workshops, and Torneo Torre de Hercules which also has classes and might have Destreza.

Okay, what if I don’t have that option and like many other HEMAists, I have to start it on my own? What resources can I find online? Where can I ask questions and discuss Destreza with other diestros?

Assuming you can’t read Spanish, I would recommend anyone interested to take a look at Tim Rivera’s translations at Spanishsword.org, starting with Díaz de Viedma‘s Epitome de la Enseñanza, and continuing with his Método de Enseñanza de Maestros. They’re both rather small books, and I found the first helps to understand the second so you can read them fully before starting to practice. After that, you can continue with the non-fully translated sources.

If going straight to the sources is a bit much Puck Curtis has some interesting stuff at destreza.us and his blog.

Right now it seems the main place to talk about Destreza in English is the Destreza in the SCA Facebook group, which is a lot less SCA specific than one might assume.

I’ve also written a limited glossary based on Rada, it was made specifically for a seminar so it includes what I thought was necessary for it only, and an intro class to Destreza which I now consider outdated, but can probably still be useful to someone starting out.

Daniel Hambraeus of UmeHFS

This has been a long talk, Aleix. I really would like to delve more into Destreza with you in the future, but, alas, we have to make this an interview, not a book. Thank you very much for your time. A final question – what does Destreza give you, personally, that you didn’t find in anything else?

I would say the cautious style meshes well with my personality, as does Rada’s more “engineer style” of terminology (when he doesn’t annoy me for being almost there but not quite), and I also find the way that everything feels quite effortless when things go well quite satisfying.

It also seems to be very much doable with little to no “frog DNA”, which is something that most of HEMA can’t say.

Thank you for having me, I’m always glad to ramble about Destreza for a while.